Our Church Challenges the UUA Establishment, 1967-1971

How our members and ministers pushed for Black Empowerment within the Unitarian Universalist Association

- Introduction -

From 1967 - 1972 our ministers and members played a leading role in pushing the Unitarian Universalist Association on issues of Black empowerment and Black self-determination. While the story of the Black Empowerment Controversy in the UUA has been described in great detail in Rev. Dr. Mark Morrison-Reed’s book, Revisiting the Empowerment Controversy, what is provided below is an account specific to our church and details the role our church played in challenging the UUA establishment on issues relating to Black empowerment. Whenever possible the words of our members and our ministers are used to tell this story.

We are proud to be part of a progressive organization of Unitarian Universalists that has a long commitment to civil rights, racial equality, and liberation. What happened in the 1960s and 70s shows that even within a progressive faith organization, our congregation is willing to use our energy and talents to push boundaries and help our well-meaning friends to consider new ways to make our churches achieve the type of equality we want to see in the world.

The written portions were drafted by Keola Whittaker as part of his final project for a course on Unitarian Universalist History at the Starr King School for the Ministry. These pages include quotes and scanned material directly from our archives. Other important information was obtained from the writings of Rev. Stephen Fritchman and Rev. Dr. Mark Morrision-Reed.

Please click here for a full bibliography and other resources.

To skip ahead, you may view the events of early 1967, late 1967, 1968, 1969, 1970, and 1971.

national Civil Rights Milestones 1963-1967

The Black Empowerment Struggle within the Unitarian Universalist Association came during intense struggles for racial equality and civil rights nationwide. Provided below is a few of the key events of the mid-1960s to place the events within our own church in context.

The 1963 Birmingham Demonstrations. Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) helped lead the Birmingham Demonstrations in 1963 to protest the city’s segregation system. Within days of the start of the demonstrations, the city obtained an injunction against the protests and the campaign decided to not comply with the court order. King was arrested and placed in solitary confinement for violating an anti-protest injunction. While imprisoned, King wrote one of his most famous works, the “Letter from a Birmingham Jail”. The Birmingham Demonstrations are remembered for the violent response of the Birmingham police and fire departments. Law enforcement officers in Birmingham used high-pressure water hoses and attack dogs against protestors, and the press showed images of these violent responses nationwide. The reporting on these events spurred President Kennedy to propose a civil rights bill in June of that same year.

The March on Washington and the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, a massive protest for civil rights, occurred in August 1963. Some 250,000 peopled gathered at the Lincoln Memorial and it was covered by thousands of members of the press. King delivered his iconic “I Have A Dream” speech as the final presenter at the March. These events laid the groundwork for passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

The Murder of Malcom X and Founding of the Black Panther Party. In early 1965, Civil Rights leader Malcom X was assassinated. His ideas contributed to the Black Power movement. The Black Panther Party was founded on a year later in Oakland, California to protect African Americans from police brutality.

The 1965 Selma to Montgomery March. In March 1965, King organized a march from Selma, Alabama, to Montgomery to protest the disenfranchisement of African Americans. The Selma to Montgomery march was met with a violence from state troopers, who used tear gas against marchers. The reaction to King’s efforts in Selma helped spur politicians in Washington to pass the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

The 1967 Long, Hot Summer. In the summer of 1967, there were more than 150 race rebellions that erupted around the country. The most famous of these occurred in Newark and Detroit, but rebellions also sprung up in New York, Minneapolis, Atlanta, Cincinnati, Boston, and Toledo. The summer of 1967 came to be known as the “Long, Hot Summer”.

unitarian universalists’ long history of fighting for equality

Unitarian Universalists have a long history of fighting for racial equality. In the mid-19th Century, both Unitarian and Universalist ministers signed antislavery declarations and members of both faiths, including our church’s founder, were abolitionists.

The separate Unitarian and Universalist churches combined in 1961 to form the Unitarian Universalist Association. It did not take long for the newly-formed UUA to continue the social justice work of Unitarians and Universalists and start to get involved the civil rights movement.

In 1963, the UUA formed the Commission on Religion and Race. At its first meeting, on July 17, 1963, the Commission voted unanimously to support the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom and used the office and personnel of the UU Fellowship for Social Justice to help coordinate a UU response. As a result, approximately 1600 UUs joined the March, including Dana Greeley, the President of the UUA.

The UUA also supported civil rights legislation, both through formal resolutions and direct action. Twenty-two UU ministers traveled to Washington to join with other religious groups in the National Convocation on Civil Rights, held on April 28, 1964 and 400 UU ministers signed a statement endorsing the 1964 Civil Rights Act, which was inserted into the Congressional Record.

UUs also participated in the civil rights march in Selma. On March 9, 1965, three of the UU ministers travelled Selma to support and participate in the March – the Revs. Orloff Miller, Clark Olsen, and James Reeb. While in Selma, the ministers were attached by white segregationists and Reeb died from the injuries he sustained. The UUA board was meeting in Boston the next day and quickly decided to adjourn in Boston and reconvene in Selma to join a second wave of UU ministers and members to bear witness and participate in the march.

Our own Stephen Fritchman was one of the ministers that travelled to Selma after the murder of James Reeb. As Fritchaman describes, within hours of the news of Reeb’s death, “a spontaneous decision was made by fellow ministers in cities around the nation, to fly to Selma” to attend Reeb’s memorial service and support King’s work in Selma. Upon his return, Fritchman delivered a sermon on what he witnessed, in which he shared:

“We saw in the South the cruel naked fascism that exists there and underlaces the social order. We must support our Black brothers in the South who live under terror from day to day and hour to hour. I feel that our denomination has had a revival of its very soul. I was never so proud of being a Unitarian; I never felt more kinship with members of other faiths: Jewish, Catholic, and Protestant alike.”

In 1966, Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. delivered the Ware Lecture at the UUA’s General Assembly. In his speech, entitled “Don’t Sleep Through the Revolution” King first recognized the involvement of many UUs in the struggle for civil rights: “There are those wonderful moments in life when you speak before a group that is so near and dear to you that you don't feel like you have to engage in the art of persuasion. You don't feel like you are in the midst of strangers. You know that you are with friends. I can assure you that I feel that way tonight.”

King encouraged the UUA to be bold and continue to reaffirm its commitment to racial equality saying that “it is necessary for the church to reaffirm over and over again the essential immorality of racial segregation.” He continued, encouraging UUs to not sleep through the revolution and stating without reservation that not taking a clear stand was morally wrong:

“Any church which affirms the morality of segregation is sleeping through the revolution. We must make it clear that segregation, whether it’s in the public schools, in housing, or in recreational facilities, or in the church itself, is morally wrong and sinful. It is not only sociologically untenable, or politically unsound, or merely economically unwise, it is morally wrong and sinful.”

The UUA also passed a “Statement of Consensus on Racial Justice” at the 1966 General Assembly which pledged Unitarian Universalists “to work to eliminate all vestiges of discrimination and segregation in (our) churches and fellowships…and to work for integration in all phases of life in the community.”

It should be noted that there was not a complete consensus on race issues within the Unitarian Universalist faith and there was more political diversity among UUs in the 1960s than there is today. Among the six UUs that were elected to Congress, four voted in favor of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, two against it. While UUs are traditionally and continue to be politically liberal, in 1966, about 34 percent of UUs identified as Republican and some of most of the most politically progressive actions within the UUA came from the urban UU churches, like ours. A survey of congregations sent by the Commission in the Fall of 1963 revealed a lack of ethnic diversity among UU congregations and only about half of those that responded indicated that their congregation “should actively seek members from racial minority groups.” Overall, urban churches like ours tended to be more racially integrated and politically progressive but a vast majority of UUs were white and there were few Black UU ministers.

THE WATTS REBELLION - 1965

The Watts Rebellion, also known as the Watts Riots, broke out in the summer of 1965 in the neighborhood of Watts, a neighborhood in Los Angeles County, several miles south of our church. The Watts Rebellion was sparked by the violent arrest of Marquette Frye, an African American man, by a white California Highway Patrol officers on suspicion of driving while intoxicated. The news of the violent actions of the arresting officers sparked six days of rioting and resulted in 34 deaths, over 1,000 injuries, and nearly 4,000 arrests. The Rebellion started on August 11, 1965, the day of Frye’s arrest, and ended on August 16, 1965.

On August 17, 1965, Fritchman, wrote an urgent letter to the church:

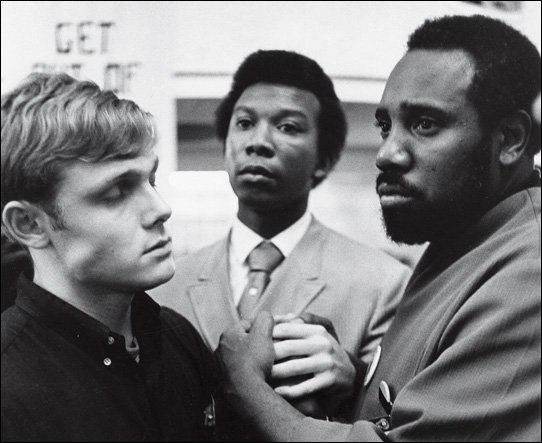

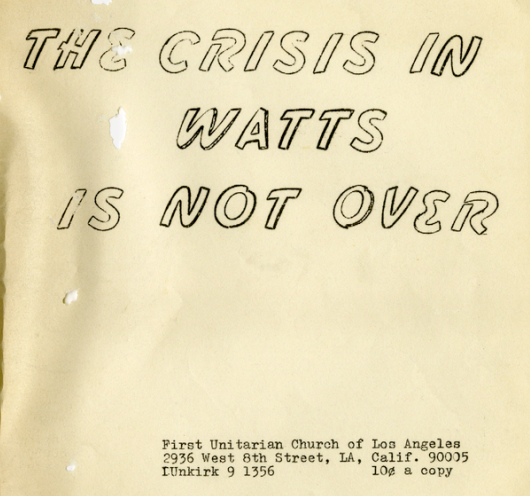

The following Sunday, Fritchman was back in the pulpit and delivered one of his most famous sermons: “The Crisis in Watts Is Not Over.” In his sermon, Fritchman called out those politicians that sought to blame the Rebellion on a series of “scapegoats” such as “the Black Muslims, outside reformers, civil disobedience agitators, or paramilitary outfits with trousers tucked in their boots.” Fritchman argued that racism and classism were at the root of the issue which resulted in the Watts Rebellion and without real change, rebellions will continue. Fritchman preached, “if we have any moral and social sanity left…we will begin to change the life of men, women, and children in Watts and elsewhere. We will tear down the slums and the store front monstrosities called business establishments. If we fail in this, Los Angeles will have more fire, more violence, because there is a point of no return.”

On August 7, 1967, Fritchman delivered another one of his well-known sermons on race, “Is There an Alternative to Black Power for the American Negro Today?” He answered this question with a definitive “No.” His sermon, delivered to a mixed-race but majority white audience, spoke directly to fears whites had with the term “Black Power”.

“The phrase ‘Black Power’ has truly shaken White America” he preached, “every sector, every class, as nothing else has been able to do since … Selma.” But “Black Power is no sinister term. It is a long overdue assertion that the power of free nations must be justly shared by all sections of the people or there will inevitably follow a just and inescapable explosion. The Italians, the Irish, and Jews have passed through such periods of building their own communities in America … and if the Negros choose to do the same thing it is their prerogative to do so.”

Fritchman also recognized that part of the process of Black empowerment may involve self-determination, community organizing, and meeting among Black communities: “Black Power may try to isolate itself and go it alone…but this may be the avenue that will have to be taken for a while. The decision lies not with black Americans alone. It is primarily with those of us who are white, and who can, if we will, make long overdue changes in acceptance of the Negro in political, economic, social and cultural areas of American life.”

Read more -> 1967: Members of Our Church Form “Black Unitarians for Radical Reform” or BURR